|

Concrete Giants on the Fore: An Industry and Competitive Analysis of the Philippine Cement Industry |

Concrete is one of those technologies that was used for centuries—in this case, by the Romans—and then had to be invented again centuries later. But once we rediscovered it, we were hooked. The only thing that humans consume more of, by volume, than water is cement.

– Sarah Laskow

I. Introduction

Far from its status as a sunset industry 20 to 30 years ago, the cement industry is now viewed by the Board of Investments-Department of Trade and Industry as a “strategic industry” with great importance to the Philippine economy. It said to embody the “single most fully integrated sector in the economy,” having strong forward linkages with most industries and the consumer market, while at the same time having an equally potent backward linkages to the mining and quarrying sectors and the communities surrounding them.

Amid this development, it is thus crucial to examine the state of competition in the cement industry. After all, a long line of literature suggests that apart from benefiting consumers, healthy competition leads to greater product variety, higher product quality and greater innovation, among others, ultimately leading to productivity growth in an industry.

The foregoing shall be the concern of this Industry and Competitive Analysis of the domestic cement industry. In particular, this paper seeks to identify and analyse the crucial elements of the cement industry, the driving forces of the industry and the determinants of competition therein. Moreover, it endeavors to provide a picture of the state of competition in the industry and point out anticompetitive behaviors that the cement industry players may be committing, in light of provisions of the the Republic Act No. 10667, otherwise known as the Philippine Competition Act.

II. Defining the Philippine Cement Industry

A. The Extent and Boundaries of the Cement Industry

1. The Players of the Industry: Then and Now

The first cement factory in the Philippines was established by Augustinian Recollects in 1914 in Binangonan, but this was shut down in 1919 due to the First World War. Prior to the Second World War, there were only two operating cement plants in the Philippines: (1) the Augustinian Recollect plant which was subsequently acquired by Don Vicente Madrigal, who named the business as Rizal Cement, and (2) a plant in Cebu operated by the Cebu Portland Cement Corporation (CEPOC), which was built with the help of the Philippine government.

After the Second World War, in light of an upsurge in the demand for cement to rehabilitate what was destroyed during the fighting, many cement plants cropped up. The major players in the industry, CEPOC, Rizal Cement Corporation, Bacnotan Cement Corporation, Republic Cement Cororation., Panay Cement Corporation, and Universal Cement Corporation, formed an organization of cement manufacturers called the Cement Institute of the Philippines.

Around the 1960s more investors got involved in the cement industry so new plants were organized and the existing ones expanded. This was also the time that the Cement Institute of the Philippines changed its name to Cement Association of the Philippines. However, because of the sudden influx of cement companies, there was an oversupply of cement, to the point that the price significantly dropped and it became unsustainable for some of the companies to stay in the market, so they were forced to close down. The notable industry player who survived this turbulent time were the cement plants of the Philippine Investments Management Consultants (PHINMA) group, the most significant of which was the Bacnotan Plant.

During the time of Martial Law, overcapacity and supply problems prevailed, leading to the creation of a government-controlled cartel, the Philippine Cement Industry Authority (PCIA) which set quotas for the different cement plants. It was also around this time that the Cement Association of the Philippines changed its name to the Philippine Cement Corp (PHILCEMCOR) which was focused on developing and fully utilizing the capabilities of existing cement plants to make them competitive for the export market. During this time, there were 17 cement plants operating in the Philippines. Among them, the Bacnotan plant was prominent for pioneering the use of coal to supply the energy needs of the cement industry.

During President Corazon Aquino’s term, the PCIA was dissolved. The price control imposed during Marcos’ time was lifted, real estate boomed again, and along with it the cement industry too. Existing cement companies, particularly the major industry players, which were the cement companies under the PHINMA group, expanded their operations.

When the Asian financial crisis hit, Philippine cement companies partnered with multinational cement corporations in order to help pay off their existing debts. This was advantageous to the Filipino firms because they were able to acquire technology and capital to improve their capabilities and adopt best practices of international corporations. The largest cement multinationals that acquired Filipino cement firms were the Financiere Lafarge S.A., Blue Circle PLC, Cemex S.A. de C.V. and Holcim Ltd. Lafarge was particularly important because in 2001, it became the world’s leading cement manufacturer and the largest conglomerate in the Philippines.

In August 2003, PHILCEMCOR changed its name into the Cement Manufacturer’s Association of the Philippines (CeMAP) with 14 founding members. It is still the current association for cement manufacturers in the Philippines, and is one of the representatives for the industry in projects and programs with the Philippine government. As of 2015, it has five members: (1) CEMEX Philippines Group of Companies, which has two corporations under it (Solid Cement Corporation and APO Cement Corporation), (2) LafargeHolcim Philippines Inc., which has seven plants operating throughout the Philippines, (3) Republic Cement and Building Materials Inc., (4) Northern Cement Corporation, and the (5) Taiheiyo Cement Philippines.

A major industry player which is not a part of CeMAP is Eagle Cement Corp. It is a company that is “majority owned and managed by the San Miguel President Corporation President Ramon Ang.” Most recently, in January 2018, Big Boss Cement Inc., a recently established 100% Filipino-owned cement firm, has entered the local cement industry. It aims to supply at least 3% if the country’s cement requirement and to employ green technology that does away with the more than century-old system of mining raw materials but rather employs an advanced system of production that utilizes lahar to produce high-quality cement.

Interestingly, the current top four industry players – LafargeHolcim, CEMEX, CRH-Aboitiz otherwise known as Republic Cement and Building Materials Inc., and Eagle Cement – account for between 80 to 82 percent of total domestic cement production. The following table provides a summary of the past and present players in the domestic cement industry.

| Table 1: Past and Present Players in the Local Cement Industry | |

| PAST PLAYERS | PRESENT PLAYERS |

| Rizal Cement;

Cebu Portland Cement Corporation; Bacnotan Cement Corporation; Republic Cement Cororation; Panay Cement Corporation; and Universal Cement Corporation

|

CEMEX Philippines Group of Companies (Solid Cement Corporation and APO Cement Corporation);

LafargeHolcim Philippines Inc.; Republic Cement and Building materials Inc.; Northern Cement Corporation; Taiheiyo Cement Philippines; Eagle Cement Corporation Big Boss Cement Inc. |

2. The Products

Currently the main types of cement available in the Philippines are Portland Cement and Blended Cement. Portland cement is a “fine, gray or white or powder manufactured using high temperature to produce calcium silicates that, in the presence of water, will undergo hydration producing a product a product that will bring aggregates to produce mortar, stucco or concrete.” Its two main raw materials are calcerous substances (e.g. chalk, limestone, marl or shells) and argillaceous elements (e.g. clay and shale). Portland cement has more specific types, classified as follows:

| Table 2: Types and Purposes of Portland Cement Manufactured in the Philippines | |

| TYPE | PURPOSE |

| Type I | It is a general purpose Portland cement that is suitable for most uses. |

| Type II | It is used for constructions in water or soil that contains moderate amounts of sulphate, or when heat build-up is a concern. |

| Type III | This cement provides and supplies high strength at an early state, usually in a week or less. |

| Type IV | It moderates heat produced by hydration that is used for massive concrete surfaces such as dams. |

| Type V | This cement resists chemical attack by soil and water high in sulfates. |

| Types IA/

IIA/ IIIA |

These are cements used to make air-entrained concrete. They have the same properties as types I, II, and III, but with the exception of possessing small quantities of air-entrained materials shared and combined with them. |

Blended cement, on the other hand “are produced by intimately and uniformly intergriding or blending two or more types of fine materials.” One of it’s primary material is actually portland cement. Blended cement also has different types, which are as follows: (1) Type IS-Portland blast furnace slag cement; (2) Type IP and Type P-Portland-pozzolan cement; (3) Type I(PM)-Pozzolan-modified portland cement; (4) Type S-Slag cement; and (5)Type I(SM)-Slag-modified portland cement.

Slag cement is a type of cement that is known for being marketed by the Iligan Cement as the “sementong may bakal”. It was even used by the said company when they had to construct the Bolkiah’s royal palace. Pozzolan and Masonry are special types of cement that were introduced by the Philippine government in the late 1970s. Pacific Cement Co., a cement company existing in the same period was the first one to create an oil-well, sulphate-resistant pozzolan cement, which was even used by the Philippine National Oil Co. (PNOC) in its oil drilling projects.

Due to the partnerships of Filipino cement firms with multinational cement conglomerates after the Asian Financial Crisis, specialized cement products entered into the market including “marine cement, cement for plastering and finishing, low-alkali and sulfate-resistant cement, cement for bricklaying and cement for foundation.”

3. Geographic Scope of the Industry Players

When PHILCEMCOR was still the industry representative, the organization “arranged for the geographical division of markets wherein the Luzon plants were to sell only in the Luzon area and the Visayas/Mindanao plants [had to] confine their sales only in [their] area.”

Today, the major industry players still have plants all over the Philippines. To be more specific, Eagle Cement has manufacturing plants in Bulacan, Cebu, and Davao; CEMEX has plants in Rizal and Cebu; LafargeHolcim has plants in La Union, Bulacan, Batangas, Iloilo, Davao and Misamis Oriental; and Republic Cement has plants in Bulacan, Batangas, Rizal, and Lanao del Norte. The location of these plants reflect the five major natural markets of the cement industry in the Philippines: (1) Northern and Central Luzon, (2) National Capital Region (NCR), (3) Southern Luzon, (4) Visayas, and (5) Mindanao.

Cemex still seems to follow the geographical division of markets implemented during PHILCEMCOR’s time. For example, its Rizal plant produces Island and Rizal brands cement which are distributed only for their customers in Luzon, and its Cebu plant produces the APO brand cement which is distributed only for their customers in the Visayas and Northern Mindanao areas. The said cement company also has a specific brand of cement sold only to customers in NCR.

Republic Cement also seems to have differentiated cement brands per region. For example, its Mindanao Pozzolan Premium is only available in Visayas and Mindanao.

B. Structural Attributes of the Cement Industry

1. Life Cycle Stage

The industry life cycle can be characterized according to five distinct phases:

| Table 3: The Five Phases of the Industry Life Cycle | |

| STAGE | CHARACTERISTIC |

| Introduction Phase | Also known as the infancy or embryonic stage, this is where early adopters of new products, technology or processes are typically carving out a niche market and developing products and services in response to an identified need. There is little to no competition unless similar companies have identified the same opportunity. |

| Growth Stage | This stage is characterized by reinvestment of the industries growing earnings into plant and equipment to meet the expanding demand and to create economies of scale. Firms active in the market are focusing on building market share and differentiating their product. |

| Maturity Stage | The phase where profitability hits a peak. Successfully positioned companies emerge as cash cows and have an abundance of cash to pay out as dividends to shareholders. New competitors enter the market at this stage to capitalize on market profitability. Price wars intensify in response to growing competition and to consolidate market share. |

| Declining Stage | The stage when some companies start to exit the industry and mergers and acquisitions hit a peak. Profitability starts to decrease and companies focus on cost cutting initiatives in the production process and streamline marketing initiatives. |

| Exit Stage | The stage where companies leave the industry, as it gets replaced by new inventions or technology which changes the industry landscape. |

Based on the foregoing descriptions of each stage of an industry life cycle, it can be said that the cement industry of the Philippines has entered another period of growth. As it stands now, the industry appears to have entered another growth stage. It is true that the cement industry is already an “old industry,” being around in the country already even before the First World War, as stated earlier. However, it is not impossible for industries to experience “rejuvenation.” Industries that may be declining already could experience a “rebirth” brought about by favorable external factors. This appears to be the case of Philippine cement indusry which, as mentioned earlier, was already considered as a “sunset industry” three to four decades ago.

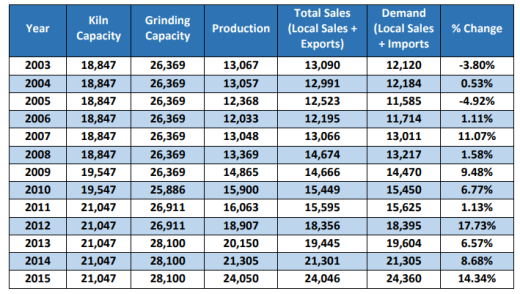

First, as can be seen in the table below, production of cement by the industry is continuously growing for the past decade, alongside the total sales and demand for the product.

Table 4: Capacity, Production, Total Sales and Total Demand for Cement in the Philippines

This can be attributed to the steady growth of the construction industry in which the cement industry indubitably plays an important role. The construction industry has undeniably experienced tremendous growth across the years and is expected to continue to grow in the coming years (see Annex). This positive development in the construction industry could have been among the positive external factors behind the “rebirth” of the once deteriorating cement industry.

Second, amid a backdrop of increasing demand, the country’s cement producers are pouring in additional investments to expand their capacity. These investments are expected to continue until 2021 and even beyond, in light of the government’s ambitious infrastructure boost. Finally, local cement makers are still vying for bigger market shares. Taken all of these, it can be said that the local cement industry has entered a new stage of growth that is expected to last in medium-term.

2. Industry Concentration

Industry concentration is a function of the number of firms in the industry and their respective market shares. One of the commonly used indices in measuring industry concentration isn the Four-Firm Concentration Ratio (CR4) which takes into account the combined market share of the four largest firms in the industry. Concerning this index, the following holds when making an interpretation of the results:

| Table 5: The Four-Firm Concentration Ratio (CR4) | ||

| MARKET SHARE OF

TOP 4 FIRMS |

DEGREE OF CONCENTRATION | INDUSTRY STRUCTURE |

| 0% | No concentration | Perfect/Monopolistic Competition |

| 0% to 50% | Low concentration | Mild Oligopoly |

| 50% to 80% | Medium concentration | Oligopoly |

| 80% to 100% | High concentration | Concentrated Oligopoly |

| 100% | Total concentration | Monopoly |

As stated earlier, as of 2017, the top four industry players of the local cement industry (LafargeHolcim, CEMEX, Republic Cement and Building Materials Inc., and Eagle Cement) account for already 80 to 82 percent of the total cement production in the Philippines. This suggests that the cement industry is a concentrated oligopoly, being composed of very few dominant firms, as asserted in past studies about the industry. As of the moment, any attempt to make an in-depth analysis of the concentration of the industry may prove to be difficult given the lack of disclosure by the firms and by the CeMAP of the individual market shares of the different cement firms in the country. At best, researchers can only rely on data reported by the media.

3. Economies of Scale

Economies of scale, in general, is achieved when more quantities of a good or service can be produced on a larger scale with only fewer input costs. It is, however, important to distinguish between internal and external economies of scale. The former is achieved when a firm reduces costs and increases production while the latter occurs in an industy-wide scale when, for instance, an entire industry’s scope of operations expands due to the creation of better transportation network or other favorable factors that generally decrease the costs for companies operating within the industry.

It appears that internal and external economies of scale have been achieved respectively, by the individual firms operating within the local cement industry, and by the industry as a whole. For the internal economies of scale, studies show that due to the mergers and acquisitions by multinational cement firms of domestic cement companies, the local cement firms were able to develop economies of scale due to structural changes imposed on them by the multinational conglomerates. The mergers and acquisitions paved the way for the local firms to absorb foreign expertise in operations and productions, shift to automated production processes, and eventually move to high productivity and equipment utilization.

For the external economies of scale, on the other hand, there is evidence showing strong coordination between the local industry players as to the monitoring of product quality, product development, sustainable development, data coordination, and reputation-building- all of which are favorable factors that could bring down costs for the industry as a whole. According to CeMAP, the following are undertaken by the association in the pursuit of promoting and lookig after the interests of its members:

| Table 6: Industry-wide Initiatives of the Local Cement Firms (CeMAP Members) to Promote a Favorable Business Environment in the Cement Industry | |

| TYPE OF INITIATIVE | PARTICULAR UNDERTAKINGS |

| Monitoring of product quality | 1. Monthly testing of each type of cement in each of the member cement plant and in three (3) retail outlets to confirm compliance with Philippine National Standards for cement;

2. Semi annual performance rating for each of the members’ cement plant of how they complied, surpassed the Philippine National Standards in their production of cement; 3. Active participation in the Bureau of Product Standards (BPS) Technical Committee 3 (TC3) composed of representatives from various government agencies, the professional sector (architects, engineers, constructors), consumer groups and the academe, that develops and formulates standards to ensure consumer welfare and protection; 4. Engagement in the proficiency testing program for cement laboratories in the Philippines to ensure accuracy in the determination of the quality of cement in the market. |

| Product development | 1. Continuing product standards review and development through the TC 3;

2. Promotion of blended cement that contributes to enhancement of environment protection and preservation; 3. Promotion of cement-based products (e.g., concrete boats, roofing tiles, etc); 4. Harmonization of PNS of BPS Standards and Blue Book or DPWH Standards |

| Sustainable development | 1. Emissions and waste management;

2. Alternative fuels and raw materials; 3. Corporate Social Responsibility; 4. Health and Safety; and 5. Formulation of guidelines to observe truck maintenance management program of delivery agents and of truck overloading. |

| Data coordination | 1. Monitoring and reporting actual cement demand;

2. Providing industry outlook by networking, linkaging with private sector, stakeholders of cement; 3. Monitoring and reporting DTI and NSO reports on cement prices nationwide; 4. Data to enable estimate of cement demand; 5. Information on local and global scenarios that may affect the industry. |

| Reputation-building | 1. The interest to be perceived as a partner of government, of the construction industry stakeholders, and of the public in general in nation building as expressed in their slogan: “Building Beyond Business”;

2. Image building through media coverage of activities and announcements; 3. Setting up website linkage with cement industry stakeholders; 4. Active participation in cement consumer associations to be updated on the issues faced by the associations (construction demand, technology, etc) affecting the use of cement; 5. Active participation in international cement associations: ASEAN Federation of Cement Manufacturers, Asian Cement Producers Amity Club, East Asia Cement Association. |

Indeed, although there are no available industry-wide statistics for the revenues, profits and costs of the local industry players, through the above enumeration of initiatives undertaken by the domestic cement firms, it can be reasonably concluded that the industry is abound with positive factors or stimuli that allow the firms, as a group, to bring down their costs while increasing or having a sustained increase in their production.

4. Product Differentiation

The Philippine cement industry boasts of different types of cement with divergent features and benefits to distinguish between the various brands of cement even within the same company. In particular, CEMEX Philippines has seven types of cement which are used for different purposes: general construction applications, plastering activities, building high strength concrete designs with minimal cement factor requirements, and for the laying of concrete hollow blocks and other types of masonry units, among others. These different types of cement have different advantages: reduced permeability, less plaster cracking, more environment-friendly, achieving early strength in less time, and superior adhesion, etc. Republic Cement, on the other hand, classifies its cement products into two types: (1) Bagged Cement and (2) Bulk Cement. Said company has five brands for its bagged cement while it has four brands for the latter classification. Meanwhile, Holcim offers four brands of its cement based on different uses as well. The brands offered by the other industry players are also classified based on their different uses.

An aspect of product differentiation is giving extra services to a company’s customers in order to keep the latter’s loyalty to their product. The players of the cement industry also do this. For example, Holcim Philippines is offering a 24-hour delivery service to its key customers.

Ultimately, there seems to be brand recognition and product differentiation in the industry especially because the varying products cater to the different particular needs of end users. Certainly, users involved in high-rise infrastructure prefer cement products with “high compressive strength and workability” as opposed to other users only involved in simple construction activities.

III. Industry Driving Forces and Determinants of Competition

A. Intensity of Rivalry

1. Synthesis and Projections in Industry Concentration

It can be reasonably said that the local cement industry is expected to remain a concentrated industry for the years ahead. It is striking that even though prospects for the industry have been good and well-reported for the past years, only one firm, Big Boss Cement Inc., has decided to enter the local cement industry. This may be attributed to the fact that there are great barriers to entry that subsist in the industry, as shall be discussed later.

In other words, although the demand for cement has been steadily increasing from 2007 and that such great demand is expected to persist in the medium-term, thereby supposedly encouraging more firms to invest in the cement industry, businesses may nonetheless find it very hard to penetrate such industry.

This situation of the cement industry nonetheless finds support in studies. Accoding to research, the structures of cement industries in many parts of the world tend to be oligopolistic, characterized by high concentration of firms and consequently, by only low to moderate rivalry.

2. Allegations of Collusive Behavior Among Industry Players

The existence of an alleged cartel in the cement industry has always baffled regulators. Collusion in the industry, which was an acceptable practice in the past in light of a government-sanctioned cartel that existed before, took place through the firms’ informal agreements to set production quotas and to assign geographic markets among themselves. This paved the way to the division of the country into different regional markets each served by particular dominant players, thereby preventing competition from taking place.

At the time when the industry was facing oversupply and low demand during the late 1990s, prices of cement remained high. Thus, price coordination among the firms was seen as the only explanation for such heightened prices. Notably, there was excess capacity in the world market during this period and imports were coming in and sold at prices lower than those charged by domestic manufacturers. However, the local cement industry vigorously resisted the entry of imports and in fact, Philcemcor even filed a dumping suit against a Taiwanese and Japanese cement corporations. The Tariff Commission, however, did not grant the request after failing to find sufficient evidence to support the industry’s request for anti-dumping measures.

The trade liberalization undertaken in the 1990s also failed to lower domestic prices of cement. This is because rather than competing against imports, domestic firms kept their prices high and worked for the imposition of safeguard measures that resulted to the reduction of import rates of cement to 0.8% in 2003 and to almost 0% in 2004. Indeed, it was ultimately concluded that imports arising from trade liberalization failed to have a “disciplining effect” on domestic firms.

In light of the foregoing, various investigations against the cement industry were conducted although failing to yield any significant resolution. In particular, during the early 2000s, the House Committee on Trade and Industry initiated investigations on the purported re-emergence of a cement cartel but no resolution has been made. Similarly, the Department of Trade and Industry also conducted investigations on the alleged collusion among local cement firms to keep cement prices above normal levels but no substantial results have come out. Consumer groups also threatened to file a criminal case against the cartel, but such case failed to prosper. Currently, there is an on-going investigation by the Philippine Competition Commission of alleged anti-competitive behavior of the firms in the cement industry. This shall be expounded later.

B. Barriers to Entry

1. Capital Requirements

The cement industry is highly capital-intensive, as it requires substantial investments in fixed assets like plants and equipment. Thus, it is hard for a smaller firm to enter into the market because there is a need for huge funding to put up cement plants and acquire the specialized equipment needed to produce cement. For example, the PHINMA Corporation, which has plans to re-enter the cement industry in the Freeport Area of Bataan, has to give an initial investment of Php 1,250,000,000.

Moreover, around 50 to 80 percent of the production cost of the industry players are spent on fuel and power to enable their plants to operate. The process that takes up around 90% of the energy consumption of these cement plants is for producing clinkers, which is a binder of the cement products. The rest of the energy are used to process raw materials and to grind the final product. Some cement firms addressed this concern by setting up their own power plants. The CeMAP members in particular have tried to replace portions of traditional fuels with alternatives, specifically, refuse-derived fuel. Thus, firms entering the industry would also have to consider in their start-up costs the establishment of own power plants.

It would have been more favorable to the analysis if there are data for the Minimum Efficient Scale (MES) of the local cement industry. The MES, which is lowest production point at which long-run total average costs (LRATC) are minimized, is an important determinant of the ease of entry into a specific industry in that “the greater the difference between the industry MES and the entry unit costs, the greater the barrier to entry.” Thus, industries with high MES deter entry of small, start-up businesses. Unfortunately there is no data for the MES of the Philippine cement industry.

2. Regulatory and Non-Regulatory Barriers

As mentioned, there used to be a Cement Industry Authority which was a regulatory body that controls all phases of the distribution and marketing of cement for the domestic and government market and gives the approval for the establishment of new cement plans or expansion of existing ones. Today, no such governmental body exists. However, there are still certain regulations that cement manufacturers need to contend themselves with. In particular, cement producers must conform with the standards set by the Bureau of Product Standards of the Department of Trade and Industry, as to the quality of the cement and related products that they are producing. Apart from this, cement manufacturers hoping to produce cement to be used in government construction projects, would have to conform to the standards set by the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). An example of an issuance by the DPWH as to cement standard is Department Order No. 133, series of 2016 where amendments to the standards specifications for portland cement concrete that would be used in pavements, are outlined.

Apart from these regulations issued by government agencies, a firm seeking to enter the industry would also need to conform with the product development standards that existing firms in the industry have already agreed to enforce among themselves. As stated earlier, members of the Cement Manufacturers’ Association of the Philippines enforce standards for cement-based products, most of which require advanced technology. These standards may require additional costs and investments on the part of the entrant firm should it aspires to catch up with the current degree of advancement of the firms already operating in the industry, and if the firm does not have enough resources to conform to the same, it may choose to decide not to enter anymore the industry.

As for non-regulatory barriers, other potent barriers to entry into the cement industry are the high costs of transportation and the limited shelf life of cement products, lasting only for about three to six months. Once a cement product has been manufactured already, it is thus imperative for a cement firm to dispose such products to their end users before its shelf life expires, otherwise, such products would only be wasted.

C. Threat of Substitutes

1. Synthesis of Product Differentiation

At the outset, cement is characterized as having a low price elasticity demand or inelastic, meaning that demand for cement does not respond much to a price changes. Thus, it can be surmised that there are not much significant substitutes available for cement in the Philippines that could thus pose competition to the cement manufacturers. This is compounded by the fact that there are different types of cement products that cater only to particular uses and by implication, to particular end-users, as mentioned earlier. Moreover, as pointed a while ago, some cement firms are also producing differentiated products that offer divergent features and benefits from other brands of cement, taking into account the varied needs of their customers. This differentation in cement products only makes it harder for other products to serve as substitutes in the goods being provided by the cement industry.

2. Product Innovation in the Cement Industry and Its Competition Implications

As of the moment, product innovations within the industry appears to be muted, thereby lessening further the prospects of alternatives to the mainstream products being sold in the market. One of the possible alternatives to the classic combination of cement, that has been explored through the initiatives of the Department of Science and Technology, is the “rice hull ash cement” which is manufactured by adding rice hull or husk to the mixture. However the use of this touted cement substitute did not take off because the end product was not as formidable as it was expected.

D. Bargaining Power of Buyers

Bargaining power of buyers refers to the pressure consumers can exert on businesses to make them provide higher quality products, better customer service, and lower prices. The bargaining power of buyers in an industry affects the competitive environment for the seller and influences the seller’s ability to achieve profitability, in a sense that strong buyers can pressure sellers to lower prices, improve product quality, and offer more and better services. Correspondingly, a weak buyer, one who is at the mercy of the seller in terms of quality and price, makes an industry less competitive and increases profit potential for the seller.

Buyers are said to be powerful if they are highly concentrated, purchase a large amount of the product, or if there is product standardization. Accordingly, the bargaining power of buyers in the Philippine cement industry is limited due foremost to the lack of substitues to cement products, the small number of cement firms in the country aggravated by the geographic segmentation of sales purportedly resorted to by some industry players, and the inelastic demand for cement.

E. External Forces Affecting Competition in the Cement Industry

1. Developments in the Construction Industry and Other Related Industries

There is an obvious direct correlation between an increase in demand in the construction industry, and the cement industry, as cement is actually an ingredient of concrete from which most of the buildings and structures built today are made out of. Thus, any positive development in the construction industry and other related industries insofar as demand for more structures, whether private or public, are concerned, would ultimately redound to more demand for cement products. This may increase the markets and opportunities for existing cement firms and in fact, the current surge in construction activities in the country has already made them vying for larger market shares and more customers, as reported in the earlier sections of the paper. Moreover, such favorable prospects in the construction industry and related industries may also attract companies capable of withstanding the high barriers to entry in the cement industry, as in the case of Big Boss Cement Inc. Indeed, assuming that there will be no under-the-table or informal agreements between the industry players as to production and market quotas, it can be said that a heightened activity in the construction sector, thereby leading to greater public and private demand for cement products, can augur well for competition since cement firms would aspire to take advantage and profit from such heightened demand. This may drive them to reduce the price of their products, further improve their operations, increase the quality of their products, intensify advertisements, and perform other legitimate business conducts that would allow them to catch a larger share of the market demand.

2. Globalization

Globalization has been a major factor that has severely affected the cement industry in the Philippines. As above mentioned, the entry of multinationals in the said industry was a significant game changer. Not only did the domestic cement companies acquire desperately needed funds to pay off their debts, but they also gained access to technological innovations that helped them become more competitive in the international market. They also gained knowledge about the best practices of international cement companies, as discussed earlier.

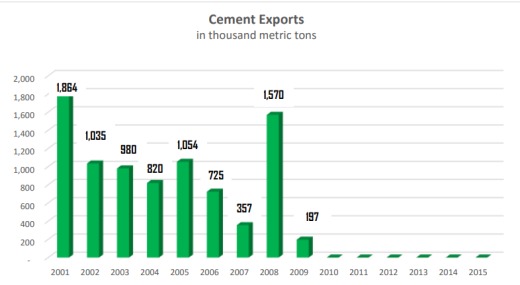

As to the international trade aspect, data show that the export and import of cement by the Philippines have been muted for the past years. The following chart shows the export of cement by the Philippines from 2001 to 2015 (the only available data so far):

Figure 1: Total Cement Exports of the Philippines from 2001 to 2015

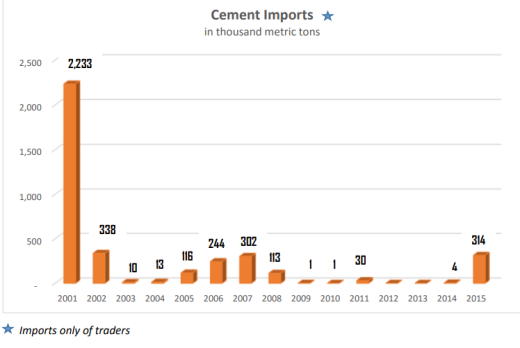

This could mean that there is no or very few excess supply of cement that could be sold in foreign markets. Meanwhile, importation of cement by the Philippines also appears to be muted as shown in this chart:

Figure 2: Total Cement Imports of the Philippines from 2001 to 2015

All of these show that the cement industry apears to be insulated form foreign trade for the past years. Considering particularly the imports data, it appears that competition from foreign cement products is very limited. This limited competition from foreign products can even be made more pronounced by the decision of the Department of Trade and Industry to issue stricter cement importation rules.

IV. Competitive Conclusion

A. State of Competition in the Cement Industry

| Table 7: Summary of the Application of Porter’s Forces of Competition in the Philippine Cement Industry | |

| DETERMINANT OF COMPETITION | APPLICATION IN THE PHILIPPINE CEMENT INDUSTRY |

| Intensity of Rivalry | Low to Moderate |

| Barriers to Entry | High; Many |

| Threat of Substitutes | Low |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Low |

| External Forces Affecting Competition | Muted |

As a synthesis, it appears that competition in the cement industry appears to be limited. Apart from the high capital requirements and fixed costs that entrant firms would have to face to enter the market, there are many regulatory and non-regulatory barriers that need to be hurdled before successfully penetrating the market. This means that even though good prospects currently abound for the cement industry in light of the growth in construction activities, very few firms may actually enter the market and pose competition to the already-existing cement firms. Moreover, there is already an existing formidable organization (CeMAP) among the established players of the industry which could serve as a platform for the existing firms to come up or impose informal barriers that would further restrict the entry of new firms to the industry. Correspondingly, this could also be one of the reasons as to why the intensity of rivalry among the local cement firms is only low. The fact that there was a past government-sanctioned cement cartel and that there were evidence alluding to collusion among the local players, does not help in the competitive picture of the industry and only serves to affirm the low intensity of rivalry in the industry.

The threat of substitute products posed by other domestic firms from other industries appears to be insignificant because of the inelastic nature of cement products and failure of the current level of research and development in the country to present other reliable alternatives. Alternative cement products from foreign markets appears to be out of the question as well given the low levels of cement importation of the country for the past years. Coupled with the oligopolistic structure of the industry, low elasticity of demand for cement products and limited foreign options, it is inevitable for Filipino cement buyers to have a low bargaining power.

B. Likely Violations of the Philippine Competition Act

As hinted earlier, the Philippine Competition Commission (PCC) is currently investigating the Philippine cement industry in light of the complaint of former trade undersecretary for consumer production Victorio Mario A. Dimagiba, who alleges that some local cement firms who happen to be members of the CeMAP, are engaging in anti-competitive agreements, effectively violating Sections 14 and 15 of the Republic Act No. 10667, otherwise known as the “Philippine Competition Act” (PCA).

Section 14 of the PCA provides, in part:

Section 14. Anti-Competitive Agreements. –

(a) The following agreements, between or among competitors, are per se prohibited:

(1) Restricting competition as to price, or components thereof, or other terms of trade;

(2) Fixing price at an auction or in any form of bidding including cover bidding, bid suppression, bid rotation and market allocation and other analogous practices of bid manipulation;

(b) The following agreements, between or among competitors which have the object or effect of substantially preventing, restricting or lessening competition shall be prohibited:

(1) Setting, Kmiting, or controlling production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(2) Dividing or sharing the market, whether by volume of sales or purchases, territory, type of goods or services, buyers or sellers or any other means; xxx

Section 15 meanwhile, which prohibits Abuse of Dominant Position, prohibits one or more entities to abuse their dominant position by engaging in conduct that would substantially prevent, restrict or lessen competition.

Given the findings in this paper, there are indeed reasonable grounds for the PCC to investigate the local cement players for alleged anticompetitive conducts. As mentioned earlier, apart from a convenient platform (the CeMAP) that would allow cement firms to come up with informal agreements that pertain to production quotas, market segmentation and other restrictive agreements, among others, the industry is marked by high concentration of firms and by significant barriers to entry that may be easily reinforced by the existing firms.

The fact that the top four firms of the industry have a cumulative market share of 80 to 82 percent, as pointed out earlier, is also worth revisiting. According to the PCA, there shall be a rebuttable presumption of market dominant position if the market share of an entity in the relevant market is at least fifty percent (50%). This means that the local cement industry is plagued with dominant firms that are susceptible to committing collective or individual acts that may be deemed as abusive of their dominant position. This is certainly not far from happening in light of the history of the local cement industry, that is marked by collusion and other implicit anticompetitive behaviors, ultimately prejudicing the welfare of Filipino cement buyers.

It is thus with great hope that the PCC be able to come up with a comprehensive and fair investigation that may finally be the key in leading to subsequent measures that would finally and truly be instrumental in revving up competition among the “concrete giants on the fore.”